Essay: The Fibonacci Learning Method

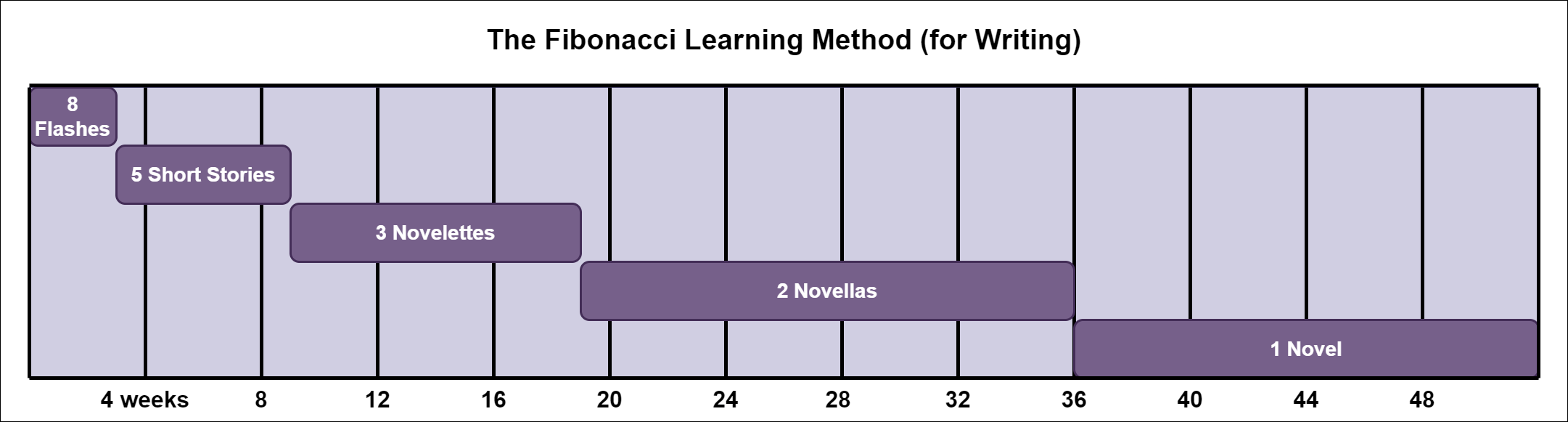

The Fibonacci Learning Method is an experimental plan to becoming an intermediate craftsman over the course of one year. Within the craft of writing, it looks like this:

- 3 (weeks) to write 8 flashes

- 6 to write 5 short stories

- 10 to write 3 novelettes

- 17 to write 2 novellas

- 16 to write 1 novel

Here’s why I think it works:

Baby Steps

If you want to become an artist do you start by painting the Sistine Chapel, or by doodling stick figures on the borders of your notebook? If you want to become a musician do you start by composing a symphony, or by humming and recording a simple tune? If you want to become a writer do you start by crafting the Illiad, or by scribbling a haiku in an afternoon?

When we learn how to do something we usually start by producing the smallest unit of that something that still carries meaning: a doodle is art; humming is music; a haiku is a poem; a short story is a story; a one-liner is a joke; and a “Hello, World!” program is a program. Each are atoms of their respective crafts, simple enough for beginners and masters alike to both create and understand. What gives a master the ability to paint the Sistine Chapel or write the Illiad is simply time and experience. (and a good sense of how long it’ll take).

The more time you dedicate to a certain task, the more experience you are likely to have gained in performing that task. In other words, time does not guarantee experience. You could read 100 books on art theory and never be able to paint the Mona Lisa. Hell, you could read 1,000 books and never be able to draw a smiley face with any amount of charm or character. Experience is failing and succeeding, but it isn’t dabbling or trying (though it does help). Experience is finishing. The fundamental unit of learning is experience, and it must be gained over time.

When a baby learns how to move, he starts by crawling. Then he learns to stand up. Then he learns to take small steps, even if he may trip and fall. When he finally gets the hang of it, he learns to walk. Then he learns to jog. Then he learns to run. And finally when he’s all grown up, he learns to sprint. But he couldn’t sprint from the beginning and he certainly didn’t learn how to do it over night.

When you’re learning how to do something you don’t start by doing the hardest version of that thing, you start by doing a simplified version of it. Then as you get the hang of it over time, you go bigger and bigger until you reach the goal. If you want to wind up sprinting, you must start by taking baby steps.

Failing Fast

The advantage of starting small is that it enables you to fail fast. Failing is not as good as succeeding but is still much better than trying. If you failed then you have probably made a big mistake or a critical error: the cake you baked is vomit-inducing; your story was unbearably boring; the portrait of your mother made her cry (and double-check herself in the mirror afterwards); or you backflipped and landed on your neck. Your brain recognizes mistakes and will adjust itself to prevent those same mistakes in the future. The size of the adjustment is typically proportional to the impact of the mistake. When you make small mistakes quickly and early you can get them out of the way, build momentum, and get to the big mistakes faster. If you’re going to write a book so bland and forgettable that you wind up on The Ellen DeGeneres Show, would you rather the process have been a two-year painstaking effort (because you had never written a book before) or a six-month writing exercise done for the sake of practice?

If you’re new to writing and your goal is to write a book, how long would it take you? Probably longer than if you were an expert writer. Let’s assume a beginner averages two pages per day while an expert averages three. In other words, the expert is 50% more productive than the beginner. If they both have one year to write a 600-page book, it’ll take the expert 200 days and the beginner 300 days to finish. That’s assuming things go according to plan. Things almost never go according to plan.

Let’s say they both get feedback and fall victim to murphy’s law: there’s a major plot hole that needs patched; readers want more from a character who doesn’t get enough page presence; there’s a boring chapter that needs to be rewritten entirely; and finally the book needs general editing and revising for clarity, tone, voice, grammar, and consistency. Considering all the changes both authors must make, they end up writing about 800 pages’ worth before the book is actually complete. It now takes the expert 267 days and the beginner 400 days to finish. Even if the beginner could suddenly work as quickly as the expert to fix his mistakes, he still couldn’t finish the book before the end of the year. Meanwhile the expert is still done with three months to spare.

Not only is the expert quicker to fix his mistakes, he’s also less likely to make them since he’s probably already made them before. He plans ahead to prevent the plotholes; he knows when to give certain characters the room to shine; he knows how to maintain excitement; and most of his writing is clear, consistent, and correct from the get-go because he writes so often. Sure he’ll still have to make edits even after the final chapter is finished, but probably much fewer than the beginner.

Now what if the beginner and expert both write just two pages? The math there is a lot simpler: it’ll take each of them just one day to finish (though the expert will have some spare time for a nap). Let’s say they both get feedback and fall victim to murphy’s law yet again, writing two terrible pages. If they’re the first two pages you’ve ever written, you might be heartbroken to hear that they suck. If you’re an expert, you’re probably not even fazed. In both cases, the solution is the same: fix it or throw it out and try again. Both options will take only one more day because it’s just two pages. If you’re a beginner, you’ve just learned the valuable lesson of creating excitement in your writing. If you’re an expert, you’ve probably only reminded yourself of this lesson but maybe you did learn something new in the process. The advantage of the beginner in this case is that it took him just as long as the expert to finish the exercise.

The Method

The Fibonacci Learning Method, which I’ll refer to as The Method, is all about momentum. It’s about leveraging the beginner’s ability to tackle small challenges quickly despite his inexperience. As he conquers small challenges he builds proficiency which allows him to tackle slightly bigger problems more quickly than if he was an absolute beginner. Tackling progressively bigger problems brings new challenges and allows for new lessons to be learned. It also helps the beginner develop a sense of how long it takes to finish something according to how ambitious it is. Eventually the beginner has enough experience that he feels ready, even if he isn’t exactly, to tackle something impressive like writing an entire book. At the end of the process, the beginner is no longer a beginner; he’s a writer, because writers write books and he has written a book.

Most crafts offer challenges of varying sizes from its most condensed form (i.e. writing a haiku) all the way to its most elaborate form (i.e. writing The Illiad). As an example, let’s look at the different categories of prose fiction which are nicely defined by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association [1]:

- Flash fiction (less than 1,000 words) [2]

- Short story (at least 1,000 words but less than 7,500 words)

- Novelette (at least 7,500 words but less than 17,500 words)

- Novella (at least 17,500 words but less than 40,000 words)

- Novel (40,000 words or more)

The Fibonacci sequence is used to define a plan of producing many smaller works, then scaling up to produce just one larger work. It was chosen because it’s a naturally occurring sequence and is already used as a means of estimating the size of tasks during scrum planning poker [3]. A calendar year is used as the length of time because it’s a natural cycle (i.e. the passing of the four seasons) and it’s a reasonable expectation to get the hang of something after doing it consistently for a year. For those who don’t have much free time or want to take things slow, a simple modification is to adjust the timespan from one to two years or anything in between. If math scares you, please skip ahead to the beautiful chart at the bottom, otherwise here’s a step-by-step breakdown of the plan:

In one year, you will write:

- 8 flashes

- 5 short stories

- 3 novelettes

- 2 novellas

- 1 novel

If we take the average word count of each category, then (in terms of words) it looks like:

- 8 * 1,000 words = 8,000 words

- 5 * 4,250 = 21,250

- 3 * 12,500 = 37,500

- 2 * 28,750 = 57,500

- 1 * 57,500 = 57,500**

- Total: 181,750

- Average/day (if you write every single day): 498

- Average/day (if you write every other day): 994

** Since a novel is defined as 40,000 words or more, we’ll say the average length is twice that of a novella (so that 2 novellas == 1 novel).

If we portion the year out according to word counts, we get:

- 4.4% (of the year) to write 8 flashes

- 11.7% to write 5 short stories

- 20.6% to write 3 novelettes

- 31.7% to write 2 novellas

- 31.6% to write 1 novel

Or in terms of weeks:

- 2.3 (weeks) to write 8 flashes

- 6.1 to write 5 short stories

- 10.7 to write 3 novelettes

- 16.5 to write 2 novellas

- 16.5 to write 1 novel

And just to give us nice whole numbers:

- 3 (weeks) to write 8 flashes

- 6 to write 5 short stories

- 10 to write 3 novelettes

- 17 to write 2 novellas

- 16 to write 1 novel

Overall, this is what the plan looks like:

The plan starts off with the beginner quickly tackling simple challenges and gradually building up to take on a complex challenge.

Flexibility

As previously mentioned this is a rigorous plan and not realistic for someone with limited free time. There is, however, room to tailor it to your needs. You can implement this plan across two years instead of one by practicing every other week instead of every week, for example. Also note that you cannot divide eight flashes across three weeks evenly but you can across two, meaning that you could write eight flashes in two weeks and take one week off to relax and reflect. This was intentional and applies to each goal category, allowing for a break week at every step in the process. If you’re extremely motivated, you could also take this week to pick up a book to learn some theory on the craft as you’re taking a break from practicing it.

Additionally you can customize the plan for any other craft. Here’s an example plan for becoming an intermediate video game developer:

- 3 (weeks) to develop 8 minigames (single mechanic i.e. Skyrim lock picking)

- 6 to develop 5 game jam entries (primary gameplay loop i.e. Flappy Bird)

- 10 to develop 3 arcade games (primary and secondary game loop i.e. Pac-Man)

- 17 to develop 2 vertical slices (primary, secondary, and tertiary game loop i.e World 1-1 of Super Mario)

- 16 to develop 1 complete game (primary, secondary, tertiary game loop, and one of: extra polish, quality of life features, an additional game mode, or more content i.e. A Short Hike)

Notice that the schedule and quantities are identical to the writing plan, but the categories have changed. Since video games don’t have word counts or any formal categories (that I could find), I took some creative liberties in defining my own. The important part is that a minigame should take about two days to finish; a game jam entry about a week (though traditionally they are made over the course of a weekend); an arcade game about 3 weeks; a vertical slice about 8 weeks (or 2 months); and a complete game about 16 weeks (or 4 months).

The Method, when framed as a way of learning video game development, is similar to the advice given by professional indie game developer Miziziziz. In a video of his titled “How to Become a Really Good Game Developer In Under a Year”, he says you should make one game in one hour, then one in two days, then one in one week, then one in two weeks, and then do it all again for a total of eight games. He then says you should make eight more games each in about a week, and that this will help you develop the important skill of finishing games. You end the plan by making a full-length game [4]. Considering he’s gone on to release five commercial indie games, his advice seems to have some empirical evidence to support it [5].

Why.

I think learning is one of the purest joys of life. For better or worse, there are more opportunities to learn in the world than you could ever experience in a single lifetime; and yet there are so many that I want to experience during mine. This essay serves as a snapshot of some of my notions about learning after having learned: how to walk, how to talk, how to read, how to write, how to ride a bike, how to play the saxophone, how to play the guitar, how to create music, how to create stories, how to program, how to study, how to speak, how to make games, how to work with others, how to fight, and through all of that, how to learn. Even now there are many crafts that I have yet to experiment with and others that I want to revisit and hone. I designed The Method as a way to let me experience as much as possible while I have the time and energy to do so. Thank you for exploring the idea with me.

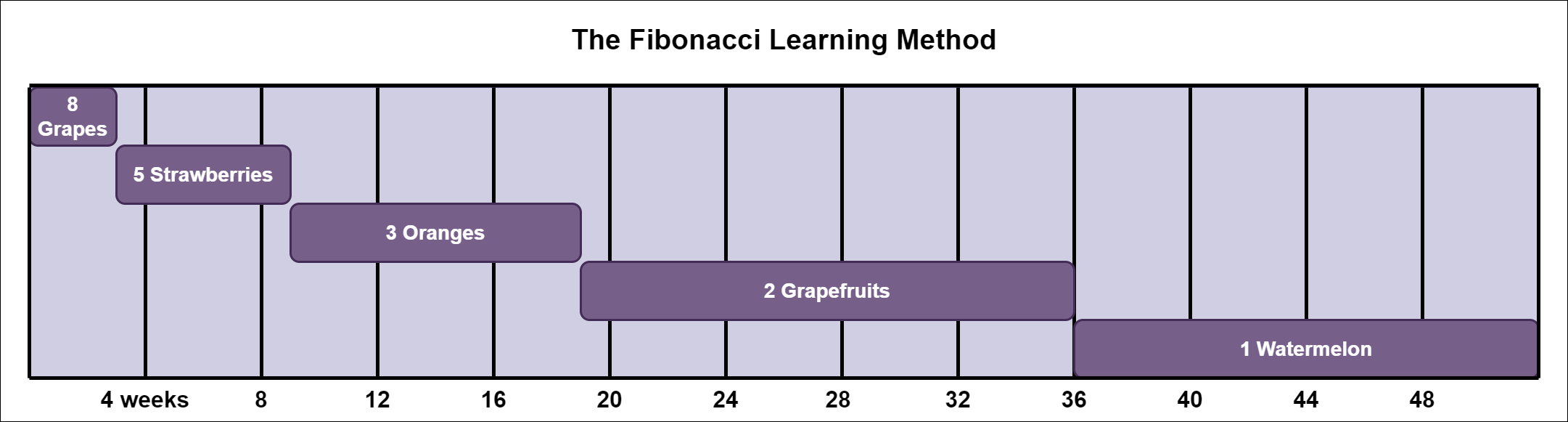

Here are some additional notes about The Method for the curious mind:

- The Method, including a diagram, with placeholder tasks:

- 3 (weeks) to finish 8 grapes

- 6 to finish 5 strawberries

- 10 to finish 3 oranges

- 17 to finish 2 grapefruit

- 16 to finish 1 watermelon

- Once the first year has ended, consider going back to baby steps so you can relearn small lessons and reinforce your sense of how long it takes to finish things.

- You should always be the first person to give yourself feedback. Make sure to review what you have done before asking someone else to review it so that you can catch and fix obvious mistakes and they can focus on giving you helpful critical feedback.

- If you’re a highly-disciplined person, taking some time away from something that you do every or almost every day is a good thing. This will give your time to reflect on what you have learned and what you still need to work on.